Seaweed forest in the ocean, a natural carbon sink that mitigates climate change

Climate change is not something we could choose to believe in or not. It is a fact. Temperatures and the sea levels are rising, droughts are longer than usual, glaciers are shrinking, seasons are not scheduled as we are used to, the sea ice is melting…

Algae could be a solution: they store CO2 releasing O2, act as natural carbon sinks and help restore the ocean as they host great biodiversity in the habitats they create. Furthermore, they serve as feed, packaging, bioenergy… The algae world is so vast and entails so many benefits in different fields that we will dedicate some articles to this species. We start here with the Seaweed Series!

Algae: feed and food

Outside the water, we tend to think of algae as food. Indeed, they can feed every living being. First of all, seaweed has become a natural fertiliser thus it is not rare to use it in crops. Microalgae (algae compounds with one cell) protect the plants and serve as a biopesticide and biostimulant, enabling seeds to grow healthy and vigorously thanks to their proteins, amino acids and minerals. In addition, they have antibacterial and antifungal attributes, which reduces the amount of artificial chemicals sprayed over the harvests.

Livestock also benefits from algae: seaweed is natural feeding with high nutritional value for animals, and a way to stop the production of the bacteria responsible for the methane that cows, pigs and sheep release. On top of that, they protect their immune system, avoiding the use of antibiotics and other drugs.

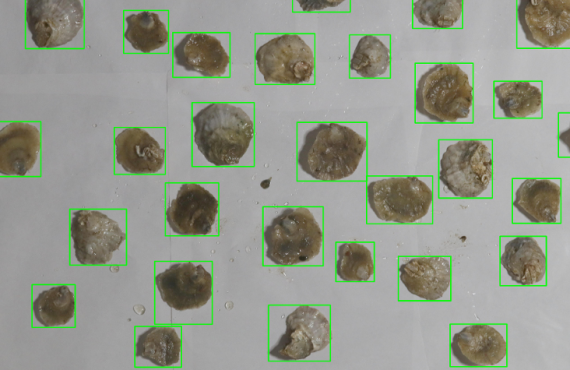

As far as aquaculture is concerned, some low-trophic species’ culture improves with algae and vice versa. Cliff Jones, a professor at Rhodes University (South Africa), explains the cycle in this video and gives the examples of the abalone and sea cucumber cultures along with Ulva and Gracilaria:

In the end, everybody wins: the farms, considering that both vegetables and animals grow more naturally and fairly; the Earth because there are less waste and pollution; and human beings, the final consumers of these products and who eat all that the rest have been fed with: the healthier our flora and fauna live, the better for them and for people.

Including algae in animals feed means increasing their welfare. This is why the integrated multitrophic systems (IMTA) work so well with seaweed: two or more species feed one another in the same space, decreasing the waste in the water, meaning a low environmental impact and lower cost when it comes to producing. Gercende Cortois de Viçose belongs to Universidad de Las Palmas de Gran Canaria (Spain) and she leads the CS land base IMTA:

Finally, human beings can eat algae as well. For thousands of years, it has been a basic ingredient in the Asian cuisine, and from the Orient, their utilisation was spread especially among those following a macrobiotic, vegan or vegetarian diet due to its healthy features: algae barely have fats, and they are full of minerals and vitamins such as A, C, B12, E and K.

Nowadays, more and more people add them in their dishes seeking an umami or salty flavour, not only an exotic one, which was up to date the main goal of chefs, restaurants or even amateur cooks who would like to enjoy sushi or ramen. Luckily, there are much more dishes for us to fancy algae. Actually, we can incorporate them almost anywhere: soups, stews, salads, omelets, juices…

If we add these sea vegetables to our menu, we will enjoy tasty dishes and benefit from algae’s properties. For example, sea spaghetti (Himanthalia elongata) has nine times more iron than lentils, while wakame (Undaria pinnatifida) provides more calcium than some diaries as well as Hijiki (Sargassum fusiforme), also rich in potassium and magnesium. That is why seaweed could be a choice for those lacking minerals or suffering from disorders such as anaemia, hypertension or hypothyroidism. On the contrary, their quantity of sodium makes them not recommendable for those with hyperthyroidism, which could be seen (for those able to eat them) as an opportunity to eliminate salt in our dishes.

They are also suitable for those wanting to lose weight: kelp (Saccharina latissima), for instance, satisfies the hunger with a very low-calorie count, while kombu (Laminaria ochroleuca) avoids weight gain because the fats become energy and they are not stored in the body. In addition, seaweed makes it easier to eliminate toxins and do not contain sugar. What they do have is fibre. Algae contain over 40% fibre and much more protein (over 15%) than other vegetables. Chlorella and Spirulina are considered as superfoods used to gain protein, vitamin B12 and iron.

Even though Asia has spread algae around the world, the truth is that its consumption is low and slow. Asia still produces and consumes the most, and outside the region, the seaweed industry is very fragmented. To enhance its production and foster the sector and its consumption, the European Commission will launch the EU4Algae in the summer.

AquaVitae, in search of sustainable aquaculture across the Atlantic, aims at optimising the culture of low-tropic species to reduce environmental impact and economic costs. Gonçalo Marinho, a researcher at CIIMAR (Porto University, Portugal), is looking for hatchery protocols for Codium and Ulva:

It is crucial to use our natural resources to mitigate climate change, aiming at a circular and blue economy. There is the need to educate people on new standards, let them know that, for example, seaweed is something they can rely on in their diets. However, algae are much more than food or feed. It has multiple utilisations. From cosmetics to bioenergy, different sectors have included this species in their products or procedures. This is just a start, the first step to more sustainable consumerism.

A deeper insight:

– Read about kelp: Learning about kelp in the Faroe islands

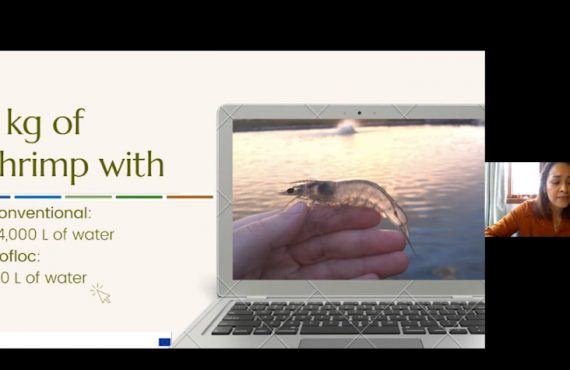

– Read about algae in a biofloc system: Cultivation of seaweeds with effluent from a shrimp biofloc rearing system