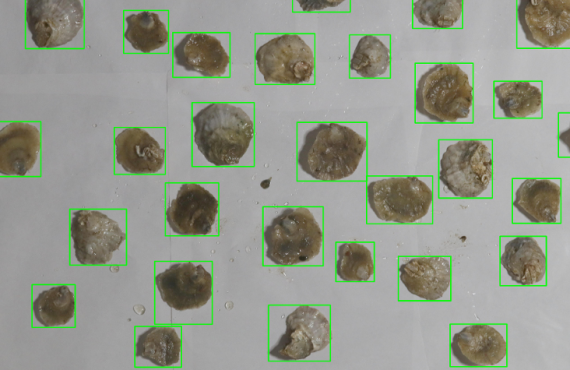

Blue mussels at Bohus Havsbruk covered by fouling. Photos by Kristina Svedberg.

By Kristina Svedberg, marine biologist at Swedish aquaculture company Bohus Havsbruk

In Sweden, aquaculture is mainly situated on the west coast, due to the inflow of high salinity water from the North Sea and the Atlantic. Here, in the coastal fjords, there are a lot of small companies farming low trophic species like sea squirts, algae, mussels and oysters. For mussels, the industry is dependent on wild spat, which is the juvenile stage of the mussel. Nets are therefore put out into the sea in early summer, when there is a high density of mussel larvae in the water. The mussels latch on to the nets and are then kept in the water for 18 months, until they reach consumption size (>5 cm).

What is fouling?

Since the mussels are grown in the ocean without any barriers, other species latch on to the nets as well. These species are known as fouling, and can be found on farms, cliffs and on your boat or jetty. For the industry, not all of these species are a problem. If there is soft-body fouling, such as an anemone, they are easily removed in the harvesting process. This is however not the case for species that produce a shell, like oysters, limpets and tube-building polychaetes. This means that the fouling can survive the harvesting and packaging process, and therefore end up in restaurants and grocery stores. Even though the quality of the mussel meat is still good, it may look unappetizing or unappealing to have worms crawling out of their tubes while you are trying to enjoy your moules frites on a sunny day by the sea.

Why is this a problem?

Due to the unappealing look of a mussel with worm fouling, farmers are often unable to sell these mussels, and instead, they become waste in the form of animal by-products. This waste is regulated by European Union law, and consequently, instead of income from the mussels, the farmer might end up with increased costs due to the waste. The severity of the fouling differs from year to year, but a farmer might lose anything between 10-80% of their yield due to the fouling of the worms.

How do we get rid of the worms?

In order to try to solve this problem, the mussel farming company Bohus Havsbruk and the Swedish environmental institute IVL are trying to investigate whether the mussels can be treated in a sustainable way to get rid of the fouling. The research is linked to Case study 9 in AquaVitae, which focuses on mussels. The new method that is being tested is a heat treatment, where the mussels are exposed to seawater that has a higher temperature than the surrounding sea, for a short amount of time. Since mussels are robust animals that can endure exposure to fluctuations in temperature, the hope is that the treatment will result in high worm mortality while still maintaining a high mussel survival.

The future of the research

The research is ongoing and at the moment it is still in its lab phase. The hope is to find a temperature in the lab trials where the goals can be achieved, and at a later stage, test the method in an upscaled field trial. If the field trial is successful, this treatment might become the key that can help mussel farmers turn their current waste into a sustainable resource for the future.

Full recording of the webinar “Fouling on blue mussels” (25 Feb 20).